Dimner

Named Man

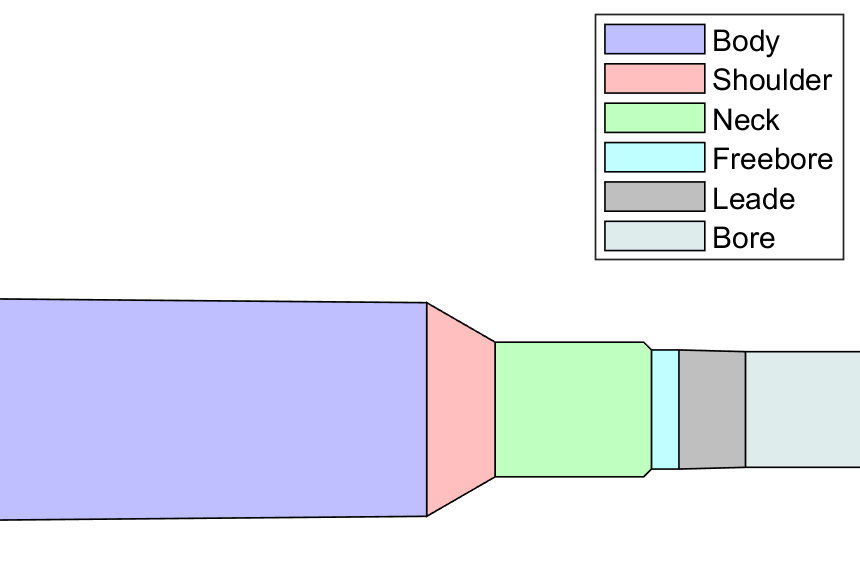

Over and over again, we all hear the term Fit is King in regards to developing a load with cast bullets The point being you need to make sure that prior to ignition a bullet optimally fits the throat (freebore/leade) area so that it can be aligned and ready to be sent down the barrel. Without an optimal fit numerous issues can arise. Leading, scattered groups, yawing, projectile deformation, just to mention a few.

I have read so many threads and posts on bullet fitting. Most of them are a treasure that deserves a sticky in a forum somewhere. Each one I read, I usually can follow along with about 90% of what is being described. I try and imagine, in my minds eye, a diagram of the round in the chamber and the bullet in the throat. Then try to apply it to my own bullet choices. This is where I always fail.

What I usually end up doing is a shotgun approach to bullet fit. Try a bunch of different mold profiles that I own, see which shoots best. Usually this corresponds to a decent, but not optimal, fitting bullet. But you know what would be cool? Being able to start with one bullet and a reasonable amount of confidence that the bullet was going to fit well. That's what I am looking to do in this thread. It comes down to a simple statement.

How does one achieve optimal bullet fit?

I honestly do not know the best way, I'm hoping you all can help me find it.

What I would like to do in this thread is take a journey on how to achieve the optimal fit. I hope that those on this forum help me with the technical terms and wording of what I am doing. To bridge that gap between the abstract language that explains Fit is King to the practical techniques, examples and advice on coming up with an optimal fit in what ever firearm you are casting bullets. So someone in the future can use this to give them a guide on how to do it for themselves. I plan on going all the way from basic terms to posting actual result targets.

It's probably going to end up being a lot more involved than I suppose, but I'm ready for the challenge. So where to begin? Well... as much as I want to just jump right into bullet profiles, throat geometry, and a bunch of stuff I can barely articulate in words... I think first we need to talk about the basics. Terminology, definitions, and the key parts of the system (for lack of a better term) that is involved with optimal bullet fit. So I guess I'll approach this as a work in progress and track each item in parts.

Pt 1: The Basics:

A - Fit is King?

B - Terminology, definitions, synonyms

C - The system ( better term?)

P.S. I'm hoping that you all will help correct me on any and all things I put in this thread. Yeah, I just wrote that. It's the internet, when have people not corrected each other? However, my goal here is 100% accuracy and consistency on this topic in a way that people can understand. Many times I think I understand what is being explained. However, after talking it through with someone, I find that I'm still missing key points. Well more often than not, they find that I'm still not getting it. That's what I will need help with.

So let's start a dialogue

I have read so many threads and posts on bullet fitting. Most of them are a treasure that deserves a sticky in a forum somewhere. Each one I read, I usually can follow along with about 90% of what is being described. I try and imagine, in my minds eye, a diagram of the round in the chamber and the bullet in the throat. Then try to apply it to my own bullet choices. This is where I always fail.

What I usually end up doing is a shotgun approach to bullet fit. Try a bunch of different mold profiles that I own, see which shoots best. Usually this corresponds to a decent, but not optimal, fitting bullet. But you know what would be cool? Being able to start with one bullet and a reasonable amount of confidence that the bullet was going to fit well. That's what I am looking to do in this thread. It comes down to a simple statement.

How does one achieve optimal bullet fit?

I honestly do not know the best way, I'm hoping you all can help me find it.

What I would like to do in this thread is take a journey on how to achieve the optimal fit. I hope that those on this forum help me with the technical terms and wording of what I am doing. To bridge that gap between the abstract language that explains Fit is King to the practical techniques, examples and advice on coming up with an optimal fit in what ever firearm you are casting bullets. So someone in the future can use this to give them a guide on how to do it for themselves. I plan on going all the way from basic terms to posting actual result targets.

It's probably going to end up being a lot more involved than I suppose, but I'm ready for the challenge. So where to begin? Well... as much as I want to just jump right into bullet profiles, throat geometry, and a bunch of stuff I can barely articulate in words... I think first we need to talk about the basics. Terminology, definitions, and the key parts of the system (for lack of a better term) that is involved with optimal bullet fit. So I guess I'll approach this as a work in progress and track each item in parts.

Pt 1: The Basics:

A - Fit is King?

B - Terminology, definitions, synonyms

C - The system ( better term?)

P.S. I'm hoping that you all will help correct me on any and all things I put in this thread. Yeah, I just wrote that. It's the internet, when have people not corrected each other? However, my goal here is 100% accuracy and consistency on this topic in a way that people can understand. Many times I think I understand what is being explained. However, after talking it through with someone, I find that I'm still missing key points. Well more often than not, they find that I'm still not getting it. That's what I will need help with.

So let's start a dialogue